|

The jingle was loud in the still air as the van appeared at the bottom of the street. "Dad! Can I have a quid?" "Don't I give you pocket money?" "Spent it!" "Go on then. Get me an ice-cream... and a pack of joints as well." He gave her a ten pound note. "You can have the change." When Kate returned she found her father waiting at the front door, his bird-watching binoculars resting on his fat belly. "What did you buy?" he demanded. "Your ice-cream. Your weed, the Moroccan you like. And a lolly for me." He took them off her and said, "Nothing else?" "Nothing!" "Turn out your pockets." She stood still, her face set in the stiff expression of captured officers in old war movies. "You're not coming back in this house, young woman, until you show me what else you got. I saw you buy it!" |

This story arose from the same discussion that also sparked "The Scaffold". Back in 1998, my friend Sean and I were both fresh-faced wannabe writers. A British magazine had announced a contest for alternate history stories, and we got together to brainstorm ideas.

As we were talking, an unfamiliar tune sounded outside Sean's window. "Is that an ice-cream van?" I asked. "I haven't heard that jingle before."

"Round here, it could be the smack van," Sean said. In those days, Sean lived in an unsalubrious corner of Leeds, full of burned-out cars and discarded syringes.

I was quite taken with the idea of an ice-cream van that delivered drugs on the side. Because we'd just been talking about alternate history, I immediately speculated that in parallel worlds, the illicit products on offer might be rather different.

This sparked the concept of an ice-cream van that travelled between alternate realities, buying products where they were legal and turning a profit by selling them where they were illegal. In our world, the van sold drugs; in the parallel world, the van sold... chocolate!

At that time, I was part of a loose scene of local writers, one of whom set up a programme of monthly readings at a café not far from where I lived. I attended the first event, where a few performers declaimed the typical mixed fare produced by wannabes and dilettantes. Afterward the organiser tried to recruit people to read at the next session. Few of the attendees volunteered, apparently because they felt they couldn't match the quality of what they'd just heard. But I confidently said, "I can do better than that — sign me up!"

This was pure reflex arrogance, and I didn't have any particular piece in mind to perform. When I subsequently thought about it, I decided I needed a story that was fairly short, so as not to tax people's patience — no more than 3,000 words — and also one that was reasonably accessible, i.e. no abstruse utopian sci-fi. Since I didn't have any completed work that fitted the criteria, I would have to write something new.

I hesitated for days, torn between various half-formed ideas. Meanwhile, the clock ticked and the date of the reading loomed ominously. I was on a deadline! Eventually I decided to write about the ice-cream van that traversed realities selling drugs and chocolate. Hastily, I bashed out a draft. Because it was aimed at public performance, I tried to make it amusing and down-to-earth.

The day of the reading arrived. The café was packed. I read out my story, and to my relief it went down reasonably well. My friend Sean acted as a claque, laughing in the right places and leading the applause at the end.

There's nothing like reciting a story in public to expose weak spots — a couple of paragraphs in the middle felt absolutely dead as I read them out. I used this experience as a guide when editing the initial draft into a submission version.

Because I thought the story had a very British tone, I didn't bother sending it to any American magazines. This may or may not have been the right decision, but it was how I felt at the time. First, I tried Interzone, who rejected it for being too funny. (In the David Pringle era, Interzone's steady diet of grey, depressing fiction earned it the affectionate nickname of Wrist-Slitters' Monthly.) Next I tried the alternate history contest that had originally sparked the idea — I never heard back from them, because the magazine folded. At this point, there weren't very many options left. In the end I sent the story to Scheherazade, a Brighton-based magazine to which I'd been subscribing for a few issues on the principle of supporting the British small press. The story was submitted in October 2000, accepted in July 2001, and published in August 2003.

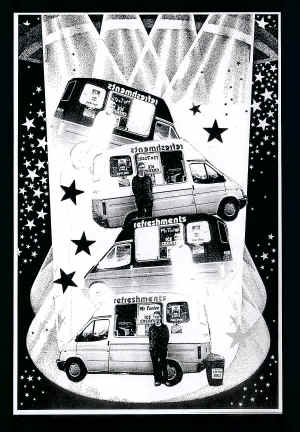

When I went to the Milford workshop in 2001, I met author Liz Williams, who told me that she'd picked "Mr Tastee" out of the slush pile when helping the editor of Scheherazade sort through submissions. Also attending was Deirdre Counihan, the magazine's art editor. I'd discovered that the British scene is a small world. At the end of the week, after completing all the workshopping, we went for a walk across Dartmoor, and Deirdre seized the opportunity of photographing me next to an ice-cream van. The magic of graphics later turned the van into Mr Tastee's reality-crossing drugs-dispensing vehicle, and this illustration accompanied the story's eventual appearance in print.

Illustration courtesy of Scheherazade

and Universe Conceptualisations